显式 null

显式 null 是一个 opt-in 特性,它修改了 Scala 的类型系统,使引用类型(继承自 AnyRef)不可为 null。

这意味着以下代码将不再能通过类型检查:

val x: String = null // error: found `Null`, but required `String`

作为替代,当要标记类型为可空时,需要使用并集类型:

val x: String | Null = null // ok

可空类型运行时可能具有 null 作为其值;因此,在不检查是否为 null 时选择其成员时不安全的。

x.trim // error: trim is not member of String | Null

显式 null 特性通过标志 -Yexplicit-nulls 启用。

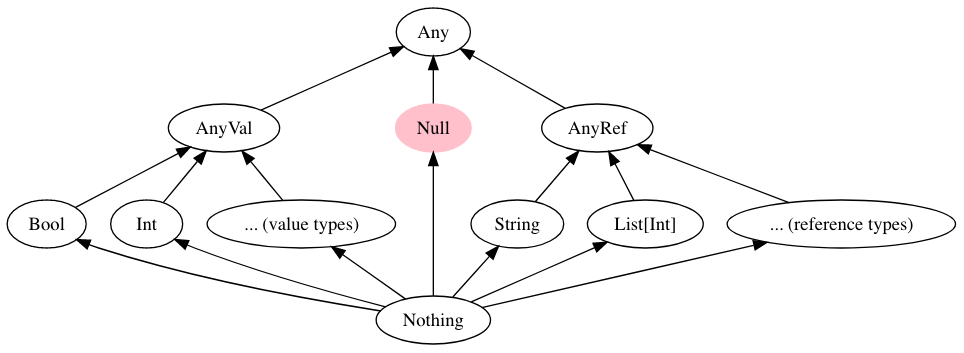

新的类型层次结构

启用显式 null 时,类型层次结构会发生变化,类型 Null 仅是 Any 的子类型, 而不再是每个引用类型的子类型,这意味着 null 不再是 AnyRef 及其子类型的值。

这是新的类型层次结构:

擦除后 Null 依然是所有引用类型的子类型(由 JVM 强制要求)。

使用 Null

为了便于使用可空值,我们建议向标准库中添加一些便捷工具。 到目前位置,我们发现以下几点非常有用:

-

一个扩展方法

.nn“抛弃”可空性extension [T](x: T | Null) { inline def nn: T = { assert(x != null) x.asInstanceOf[T] } }这意味着给定

x: String | Null,x.nn的类型为String,所以我们可以在上面调用它的所有常用方法。 当然,当x为null时会抛出一个 NPE。不要再可变变量上使用

.nn,因为它可能会在变量的类型中引入未知类型。 -

一个

unsafeNulls语言特性。当导入它时,

T | Null可以作为T使用,类似于常规的 Scala(无显式 null)。参见 UnsafeNulls 部分查看更多详情。

Unsoundness

新类型系统在关于 null 的方面是 unsound 的。 这意味着仍然存在表达式具有不可为 null的类型,譬如 String, 而其值实际上是 null。

The unsoundness happens because uninitialized fields in a class start out as null:

class C {

val f: String = foo(f)

def foo(f2: String): String = f2

}

val c = new C()

// c.f == "field is null"

编译器可以通过选项 -Ysafe-init 捕获到以上的 unsoundness。 更多细节可以在安全初始化一节找到。

Equality

We don’t allow the double-equal (== and !=) and reference (eq and ne) comparison between AnyRef and Null anymore, since a variable with a non-nullable type cannot have null as value. null can only be compared with Null, nullable union (T | Null), or Any type.

For some reason, if we really want to compare null with non-null values, we have to provide a type hint (e.g. : Any).

val x: String = ???

val y: String | Null = ???

x == null // error: Values of types String and Null cannot be compared with == or !=

x eq null // error

"hello" == null // error

y == null // ok

y == x // ok

(x: String | Null) == null // ok

(x: Any) == null // ok

Java 兼容性

The Scala compiler can load Java classes in two ways: from source or from bytecode. In either case, when a Java class is loaded, we “patch” the type of its members to reflect that Java types remain implicitly nullable.

Specifically, we patch

-

the type of fields

-

the argument type and return type of methods

We illustrate the rules with following examples:

-

The first two rules are easy: we nullify reference types but not value types.

class C { String s; int x; }==>

class C { val s: String | Null val x: Int } -

We nullify type parameters because in Java a type parameter is always nullable, so the following code compiles.

class C<T> { T foo() { return null; } }==>

class C[T] { def foo(): T | Null }Notice this is rule is sometimes too conservative, as witnessed by

class InScala { val c: C[Bool] = ??? // C as above val b: Bool = c.foo() // no longer typechecks, since foo now returns Bool | Null } -

We can reduce the number of redundant nullable types we need to add. Consider

class Box<T> { T get(); } class BoxFactory<T> { Box<T> makeBox(); }==>

class Box[T] { def get(): T | Null } class BoxFactory[T] { def makeBox(): Box[T] | Null }Suppose we have a

BoxFactory[String]. Notice that callingmakeBox()on it returns aBox[String] | Null, not aBox[String | Null] | Null. This seems at first glance unsound (“What if the box itself hasnullinside?”), but is sound because callingget()on aBox[String]returns aString | Null.Notice that we need to patch all Java-defined classes that transitively appear in the argument or return type of a field or method accessible from the Scala code being compiled. Absent crazy reflection magic, we think that all such Java classes must be visible to the Typer in the first place, so they will be patched.

-

We will append

Nullto the type arguments if the generic class is defined in Scala.class BoxFactory<T> { Box<T> makeBox(); // Box is Scala-defined List<Box<List<T>>> makeCrazyBoxes(); // List is Java-defined }==>

class BoxFactory[T] { def makeBox(): Box[T | Null] | Null def makeCrazyBoxes(): java.util.List[Box[java.util.List[T] | Null]] | Null }In this case, since

Boxis Scala-defined, we will getBox[T | Null] | Null. This is needed because our nullability function is only applied (modularly) to the Java classes, but not to the Scala ones, so we need a way to tellBoxthat it contains a nullable value.The

Listis Java-defined, so we don’t appendNullto its type argument. But we still need to nullify its inside. -

We don’t nullify simple literal constant (

final) fields, since they are known to be non-nullclass Constants { final String NAME = "name"; final int AGE = 0; final char CHAR = 'a'; final String NAME_GENERATED = getNewName(); }==>

class Constants { val NAME: String("name") = "name" val AGE: Int(0) = 0 val CHAR: Char('a') = 'a' val NAME_GENERATED: String | Null = getNewName() } -

We don’t append

Nullto a field nor to a return type of a method which is annotated with aNotNullannotation.class C { @NotNull String name; @NotNull List<String> getNames(String prefix); // List is Java-defined @NotNull Box<String> getBoxedName(); // Box is Scala-defined }==>

class C { val name: String def getNames(prefix: String | Null): java.util.List[String] // we still need to nullify the paramter types def getBoxedName(): Box[String | Null] // we don't append `Null` to the outmost level, but we still need to nullify inside }The annotation must be from the list below to be recognized as

NotNullby the compiler. CheckDefinitions.scalafor an updated list.// A list of annotations that are commonly used to indicate // that a field/method argument or return type is not null. // These annotations are used by the nullification logic in // JavaNullInterop to improve the precision of type nullification. // We don't require that any of these annotations be present // in the class path, but we want to create Symbols for the // ones that are present, so they can be checked during nullification. @tu lazy val NotNullAnnots: List[ClassSymbol] = ctx.getClassesIfDefined( "javax.annotation.Nonnull" :: "edu.umd.cs.findbugs.annotations.NonNull" :: "androidx.annotation.NonNull" :: "android.support.annotation.NonNull" :: "android.annotation.NonNull" :: "com.android.annotations.NonNull" :: "org.eclipse.jdt.annotation.NonNull" :: "org.checkerframework.checker.nullness.qual.NonNull" :: "org.checkerframework.checker.nullness.compatqual.NonNullDecl" :: "org.jetbrains.annotations.NotNull" :: "lombok.NonNull" :: "io.reactivex.annotations.NonNull" :: Nil map PreNamedString)

Override check

When we check overriding between Scala classes and Java classes, the rules are relaxed for Null type with this feature, in order to help users to working with Java libraries.

Suppose we have Java method String f(String x), we can override this method in Scala in any of the following forms:

def f(x: String | Null): String | Null

def f(x: String): String | Null

def f(x: String | Null): String

def f(x: String): String

Note that some of the definitions could cause unsoundness. For example, the return type is not nullable, but a null value is actually returned.

Flow Typing

We added a simple form of flow-sensitive type inference. The idea is that if p is a stable path or a trackable variable, then we can know that p is non-null if it’s compared with null. This information can then be propagated to the then and else branches of an if-statement (among other places).

Example:

val s: String | Null = ???

if s != null then

// s: String

// s: String | Null

assert(s != null)

// s: String

A similar inference can be made for the else case if the test is p == null

if (s == null)

// s: String | Null

else

// s: String

== and != is considered a comparison for the purposes of the flow inference.

Logical Operators

We also support logical operators (&&, ||, and !):

val s: String | Null = ???

val s2: String | Null = ???

if (s != null && s2 != null) {

// s: String

// s2: String

}

if (s == null || s2 == null) {

// s: String | Null

// s2: String | Null

} else {

// s: String

// s2: String

}

Inside Conditions

We also support type specialization within the condition, taking into account that && and || are short-circuiting:

val s: String | Null = ???

if s != null && s.length > 0 then // s: String in `s.length > 0`

// s: String

if s == null || s.length > 0 then // s: String in `s.length > 0`

// s: String | Null

else

// s: String

Match Case

The non-null cases can be detected in match statements.

val s: String | Null = ???

s match {

case _: String => // s: String

case _ =>

}

Mutable Variable

We are able to detect the nullability of some local mutable variables. A simple example is:

class C(val x: Int, val next: C | Null)

var xs: C | Null = C(1, C(2, null))

// xs is trackable, since all assignments are in the same method

while (xs != null) {

// xs: C

val xsx: Int = xs.x

val xscpy: C = xs

xs = xscpy // since xscpy is non-null, xs still has type C after this line

// xs: C

xs = xs.next // after this assignment, xs can be null again

// xs: C | Null

}

When dealing with local mutable variables, there are two questions:

-

Whether to track a local mutable variable during flow typing. We track a local mutable variable if the variable is not assigned in a closure. For example, in the following code

xis assigned to by the closurey, so we do not do flow typing onx.var x: String | Null = ??? def y = { x = null } if (x != null) { // y can be called here, which would break the fact val a: String = x // error: x is captured and mutated by the closure, not trackable } -

Whether to generate and use flow typing on a specific use of a local mutable variable. We only want to do flow typing on a use that belongs to the same method as the definition of the local variable. For example, in the following code, even

xis not assigned to by a closure, we can only use flow typing in one of the occurrences (because the other occurrence happens within a nested closure).var x: String | Null = ??? def y = { if (x != null) { // not safe to use the fact (x != null) here // since y can be executed at the same time as the outer block val _: String = x } } if (x != null) { val a: String = x // ok to use the fact here x = null }

See more examples.

Currently, we are unable to track paths with a mutable variable prefix. For example, x.a if x is mutable.

Unsupported Idioms

We don’t support:

- flow facts not related to nullability (

if x == 0 then { // x: 0.type not inferred }) -

tracking aliasing between non-nullable paths

val s: String | Null = ??? val s2: String | Null = ??? if (s != null && s == s2) { // s: String inferred // s2: String not inferred }

UnsafeNulls

It is difficult to work with many nullable values, we introduce a language feature unsafeNulls. Inside this “unsafe” scope, all T | Null values can be used as T.

Users can import scala.language.unsafeNulls to create such scopes, or use -language:unsafeNulls to enable this feature globally (for migration purpose only).

Assume T is a reference type (a subtype of AnyRef), the following unsafe operation rules are applied in this unsafe-nulls scope:

-

the members of

Tcan be found onT | Null -

a value with type

Tcan be compared withT | NullandNull -

suppose

T1is not a subtype ofT2using explicit-nulls subtyping (whereNullis a direct subtype of Any), extension methods and implicit conversions designed forT2can be used forT1ifT1is a subtype ofT2using regular subtyping rules (whereNullis a subtype of every reference type) -

suppose

T1is not a subtype ofT2using explicit-nulls subtyping, a value with typeT1can be used asT2ifT1is a subtype ofT2using regular subtyping rules

Addtionally, null can be used as AnyRef (Object), which means you can select .eq or .toString on it.

The program in unsafeNulls will have a similar semantic as regular Scala, but not equivalent.

For example, the following code cannot be compiled even using unsafe nulls. Because of the Java interoperation, the type of the get method becomes T | Null.

def head[T](xs: java.util.List[T]): T = xs.get(0) // error

Since the compiler doesn’t know whether T is a reference type, it is unable to cast T | Null to T. A .nn need to be inserted after xs.get(0) by user manually to fix the error, which strips the Null from its type.

The intention of this unsafeNulls is to give users a better migration path for explicit nulls. Projects for Scala 2 or regular Scala 3 can try this by adding -Yexplicit-nulls -language:unsafeNulls to the compile options. A small number of manual modifications are expected. To migrate to the full explicit nulls feature in the future, -language:unsafeNulls can be dropped and add import scala.language.unsafeNulls only when needed.

def f(x: String): String = ???

def nullOf[T >: Null]: T = null

import scala.language.unsafeNulls

val s: String | Null = ???

val a: String = s // unsafely convert String | Null to String

val b1 = s.trim // call .trim on String | Null unsafely

val b2 = b1.length

f(s).trim // pass String | Null as an argument of type String unsafely

val c: String = null // Null to String

val d1: Array[String] = ???

val d2: Array[String | Null] = d1 // unsafely convert Array[String] to Array[String | Null]

val d3: Array[String] = Array(null) // unsafe

class C[T >: Null <: String] // define a type bound with unsafe conflict bound

val n = nullOf[String] // apply a type bound unsafely

Without the unsafeNulls, all these unsafe operations will not be type-checked.

unsafeNulls also works for extension methods and implicit search.

import scala.language.unsafeNulls

val x = "hello, world!".split(" ").map(_.length)

given Conversion[String, Array[String]] = _ => ???

val y: String | Null = ???

val z: Array[String | Null] = y

Binary Compatibility

Our strategy for binary compatibility with Scala binaries that predate explicit nulls and new libraries compiled without -Yexplicit-nulls is to leave the types unchanged and be compatible but unsound.